Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis (AGEP): Recognizing and Managing a Rapid-Onset Drug Rash

Drug Reaction Risk Checker

Is Your Medication a Potential AGEP Trigger?

AGEP (Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis) is a rare but serious drug reaction. This tool helps identify medications that might trigger AGEP based on current medical knowledge.

Select Your Recent Medication

Risk Assessment Results

- Stop taking the medication immediately

- Consult your doctor or urgent care immediately

- Bring a list of all recent medications

Imagine waking up with your skin covered in tiny white bumps, burning and itchy, just two days after taking a common antibiotic. Your doctor says it’s a rash. But this isn’t your typical allergy. It’s AGEP-Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis-a rare but dangerous reaction triggered by medication. Unlike hives or mild eczema, AGEP comes on fast, looks alarming, and demands quick action. It’s not common-only 1 to 5 people per million get it each year-but when it happens, knowing what to do can mean the difference between a quick recovery and serious complications.

What AGEP Actually Looks Like

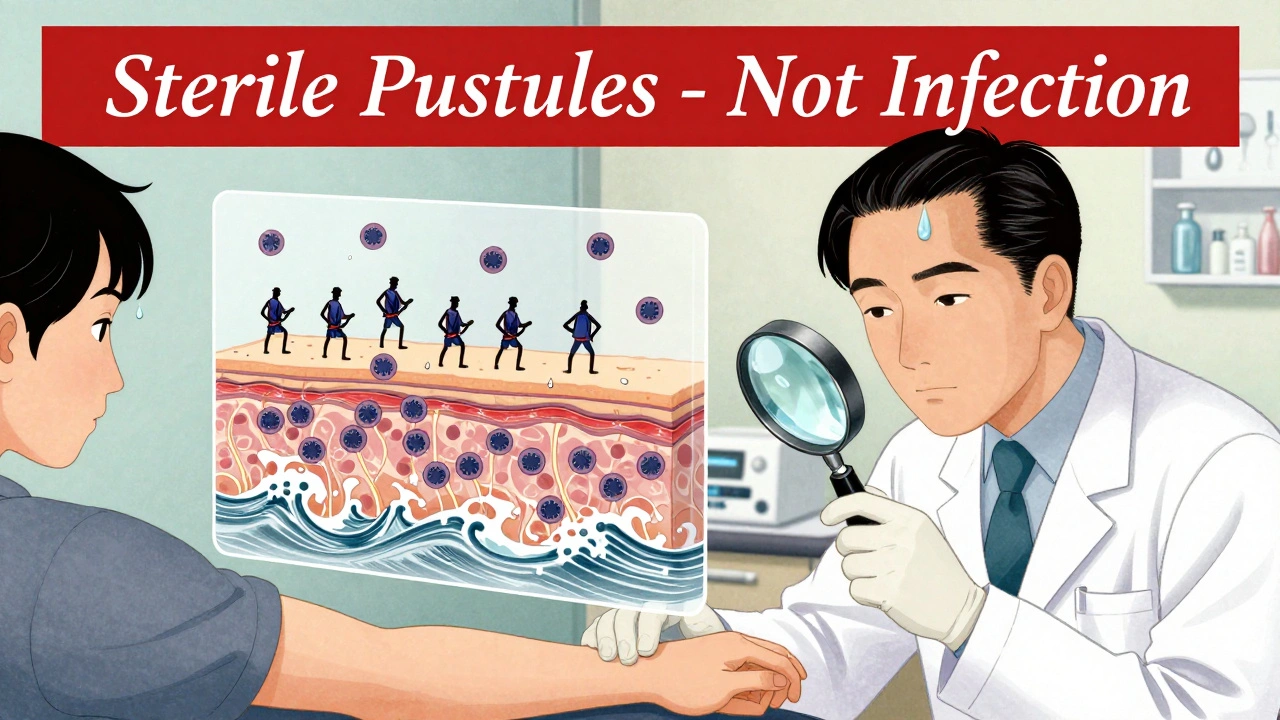

AGEP doesn’t creep in. It hits hard. Within 24 to 48 hours after taking a drug, hundreds of small, sterile pustules-each about the size of a pinhead-appear across the skin. They start in warm, moist areas: under the arms, in the groin, or on the face. Then they spread quickly, covering large parts of the body. The skin underneath is bright red and tender. Fever often spikes above 38.5°C. You might feel like you’re coming down with the flu, but your body isn’t fighting an infection-it’s reacting to a drug.What makes AGEP stand out is that these pustules aren’t infected. No bacteria live inside them. They’re filled with white blood cells, mostly neutrophils, pushed to the surface by inflammation. Under a microscope, the skin shows swelling in the upper layers and clusters of these cells just below the outermost layer. That’s why antibiotics won’t help. Treating it like an infection makes things worse.

It’s easy to confuse AGEP with psoriasis or even heat rash. But there’s a key difference: AGEP rarely affects the palms and soles. Generalized pustular psoriasis does. And psoriasis usually has a history-patients often have plaques or family members with the condition. AGEP? Usually, it’s the first time the skin has ever acted up like this. That’s why diagnosis often gets delayed. Studies show up to 40% of cases in community clinics are misdiagnosed.

What Causes AGEP?

Over 90% of AGEP cases are caused by drugs. The most common offenders? Antibiotics. Specifically, amoxicillin-clavulanate, which accounts for nearly a third of all cases. Other antibiotics like macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin) and sulfonamides are also frequent triggers. But it’s not just antibiotics. Antifungal pills, calcium channel blockers (used for high blood pressure), and even some NSAIDs can set it off. In rare cases, it’s triggered by infections or even vaccines-but drugs are the main culprit.One surprising fact: AGEP can happen even with medications you’ve taken before without issue. There’s no warning. You could take amoxicillin for a sinus infection three times before-and then, on the fourth time, your body flips a switch. That’s why it’s so hard to predict. Researchers are starting to find genetic links. One variant, HLA-B*59:01, is tied to higher risk in Asian populations. People with this gene are nearly nine times more likely to develop AGEP after certain drugs. Screening for this isn’t routine yet-but it might be soon.

How AGEP Is Diagnosed

There’s no single blood test for AGEP. Diagnosis comes from three things: what the skin looks like, what you’ve taken recently, and lab results. Doctors look for the classic pattern: sudden pustules on red skin, starting in skin folds. They check your fever and ask about medications taken in the last 1 to 14 days. The median time from drug exposure to rash? Just two days.Lab work usually shows high white blood cell counts-with neutrophils making up more than 75% of them. C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation, is also elevated. A skin biopsy confirms it: pustules just under the top layer of skin, no signs of infection, lots of neutrophils. In 2023, the EuroSCAR group rolled out a new scoring tool called AGEP 2.0. It uses seven clinical features to calculate your chance of having AGEP. With 94% sensitivity and 89% specificity, it’s becoming the gold standard in hospitals.

What’s not needed? Allergy skin tests. They don’t work for AGEP. It’s not an IgE-mediated reaction like anaphylaxis. It’s a neutrophil-driven storm. That’s why stopping the drug is the only surefire step.

Treatment: Stop the Drug-and Then What?

The most important thing you can do? Stop the drug immediately. That’s it. No exceptions. In over 90% of cases, the rash clears up on its own within 10 to 14 days after stopping the trigger. Supportive care helps you feel better while your body heals. Cool compresses, moisturizers, and antihistamines for itching are standard. Some patients need IV fluids if they’re dehydrated from fever.But here’s where things get messy: should you use steroids?

There’s a big divide in the medical community. Some experts, especially in North America, say no. They point out that AGEP is self-limiting. Giving steroids might mask symptoms or increase infection risk. One team at Baylor College of Medicine saw 15 cases over three years and never used systemic steroids-everyone recovered fine.

But European experts say yes, especially if the rash covers more than 20% of your body or you’re very sick. A 2023 study showed patients treated with oral prednisone (0.5 to 1 mg per kg per day) recovered in about 7 days, compared to 11 days without steroids. That’s a 4-day difference. And in severe cases, steroids can prevent complications like sepsis or organ stress.

So what’s the real answer? It depends. If you’re otherwise healthy with mild AGEP, skip the steroids. If you’re older, have diabetes, or the rash is widespread, steroids might be worth the risk. The American Journal of Clinical Dermatology says it best: “The decision should be individualized.”

New Hope: Biologics for Tough Cases

For the rare patients who don’t improve-or who can’t take steroids because of other health problems-there’s a new option: biologics. Specifically, drugs that block interleukin-17 (IL-17), like secukinumab.In one case, a patient with AGEP triggered by amoxicillin couldn’t take steroids due to uncontrolled diabetes. Within 48 hours of a single injection of secukinumab, the pustules vanished. Another patient saw complete clearing in 72 hours. These aren’t flukes. In early trials, 92% of patients responded to secukinumab with no serious side effects. The drug, already approved for psoriasis, is now being tested in phase II trials specifically for AGEP (NCT04876231).

Why does this work? Because AGEP isn’t just a rash-it’s an overactive immune signal. IL-17 is the chemical that tells neutrophils to swarm the skin. Block it, and the storm stops. This could change how we treat severe cases. No more waiting two weeks to heal. No more hospital stays. Just one shot.

Recovery and Long-Term Risks

Most people recover fully. The mortality rate is low-just 2% to 4%. That’s far better than Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, which kills up to 25% of patients. But recovery isn’t just about the rash fading. The skin peels off 7 to 10 days after the pustules appear. This is the desquamation phase. It’s not dangerous, but it’s uncomfortable. Dry, flaky skin can crack and bleed.Patients who get written instructions on moisturizing and sun protection are twice as likely to follow them. That’s huge. Sun exposure during healing can cause long-term dark spots. Emollients with ceramides help rebuild the skin barrier. Avoid harsh soaps. Don’t scratch. These steps matter.

Long-term, the biggest risk is re-exposure. Once you’ve had AGEP from a drug, you’re at high risk of getting it again if you take it-or even a similar one. Doctors must document the trigger clearly in your chart. Pharmacists need to flag it in their systems. But in community hospitals, that doesn’t always happen. That’s why patients should keep a personal list of all medications that caused reactions-write it down, carry it with you.

What’s Next for AGEP?

Research is accelerating. The International Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (RegiSCAR) has tracked over 300 AGEP cases since 2020. They’re tracking long-term outcomes, looking for patterns in who gets it and why. The European Medicines Agency now requires drug makers to monitor for AGEP in clinical trials for antibiotics and heart medications. Drug labels are changing-amoxicillin-clavulanate now lists AGEP as a possible side effect.Future tools may include genetic screening for high-risk patients before prescribing. A simple blood test for HLA-B*59:01 could prevent AGEP in Asian populations before it starts. And biologics like secukinumab might soon be approved as first-line treatment for severe cases, not just a last resort.

For now, the message is clear: if you develop a sudden pustular rash after starting a new drug, stop it. Get seen. Don’t wait. AGEP is rare-but it’s serious. And the faster you act, the faster you’ll heal.

Can AGEP be caused by over-the-counter medications?

Yes. While antibiotics are the most common trigger, AGEP can also be caused by over-the-counter drugs like NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen), antifungal pills (terbinafine), and even some herbal supplements. Any medication that affects the immune system or triggers neutrophil activity has the potential to cause AGEP.

Is AGEP contagious?

No. AGEP is not contagious. The pustules contain no bacteria or virus-they’re made of your own immune cells. You cannot spread it to others through touch, air, or bodily fluids. It’s a reaction inside your body, not an infection.

How long does it take to recover from AGEP?

Most people recover fully within 10 to 14 days after stopping the triggering drug. The pustules usually peak within 2 to 3 days, then begin to dry up. Skin peeling follows around day 7 to 10. Fever and discomfort typically improve within 48 to 72 hours after discontinuing the medication.

Can you get AGEP more than once?

Yes. Once you’ve had AGEP from a specific drug, you’re at high risk of developing it again if you take that same drug-or even one in the same class. For example, if amoxicillin-clavulanate caused your AGEP, you should avoid all penicillin-based antibiotics. Cross-reactivity is common, so always inform your doctors and pharmacists of your history.

Should I avoid all antibiotics after having AGEP?

No-not all antibiotics. Only the one that triggered your reaction and closely related drugs. For example, if amoxicillin caused it, avoid other penicillins and possibly cephalosporins. But you can likely still safely take macrolides like azithromycin or tetracyclines like doxycycline, unless they’re also known triggers. Always get tested or consult a dermatologist or allergist before restarting any medication.

Is AGEP the same as acne or folliculitis?

No. Acne and folliculitis involve hair follicles and are often caused by bacteria or oil buildup. AGEP pustules are not follicular-they appear randomly across the skin, even on areas without hair. They’re sterile, appear suddenly, and are accompanied by fever and widespread redness. The timing and pattern are completely different.

What to Do If You Suspect AGEP

If you notice a sudden rash with small white bumps and fever after starting a new drug:- Stop taking the medication immediately.

- Call your doctor or go to an urgent care center. Don’t wait.

- Bring a list of all recent medications-even vitamins or supplements.

- Take a photo of the rash. Visuals help doctors diagnose faster.

- Stay hydrated and avoid hot showers or scrubbing your skin.

- Do not apply steroid creams without medical advice-some can worsen the reaction.

Early recognition saves time, reduces hospital stays, and prevents complications. AGEP is rare-but it’s real. And knowing what to look for can save your skin-and your health.

joanne humphreys

December 5, 2025 AT 20:02After reading this, I finally understand why my cousin’s rash disappeared so fast after they stopped the amoxicillin. I thought it was just a bad allergy. This is eye-opening-no one ever explained the neutrophil part. I’m going to print this out for my mom’s doctor next time she gets a weird rash.

Mansi Bansal

December 7, 2025 AT 07:42It is of paramount importance to underscore that the pathophysiological mechanism underlying AGEP is not merely a dermatological phenomenon, but rather a systemic immune dysregulation event of considerable clinical gravity. The absence of bacterial etiology, coupled with the neutrophilic infiltration pattern, necessitates a paradigmatic shift in therapeutic protocol. One cannot, under any circumstance, conflate this entity with benign cutaneous eruptions such as folliculitis or acne vulgaris.

Kay Jolie

December 7, 2025 AT 22:02Okay but have you SEEN the IL-17 blockade data?? Like, secukinumab is basically a magic bullet for AGEP now. We’re talking about going from ‘wait two weeks for your skin to peel off’ to ‘one shot and poof-skin looks normal.’ This isn’t just medicine, this is sci-fi becoming real. Someone call the FDA, we need this approved yesterday. I’m already imagining the TikTok videos: ‘My AGEP vanished in 72 hours 🤯 #BiologicsAreLife’

Billy Schimmel

December 8, 2025 AT 08:26So… we’re saying the whole steroid debate is just doctors arguing over who gets to be the boss? Cool. I’ll just stop the drug and use lotion. Thanks for the overcomplicated article, I guess.

Max Manoles

December 9, 2025 AT 23:28The AGEP 2.0 scoring tool is a significant advancement in clinical diagnostics. Its 94% sensitivity and 89% specificity, as referenced from the EuroSCAR group’s 2023 validation study, provide a robust framework for early differentiation from generalized pustular psoriasis and other neutrophilic dermatoses. The inclusion of temporal drug exposure windows and clinical localization patterns enhances inter-rater reliability. This should be integrated into EMR systems as a decision support module.

Clare Fox

December 10, 2025 AT 04:11so like… we’re all just walking around with immune systems that could randomly flip out because of a pill we’ve taken 3 times before? and no one knows why? i mean… that’s kinda terrifying. also why is everyone so obsessed with steroids? just stop the drug. why complicate it.

Akash Takyar

December 10, 2025 AT 23:01It is encouraging to note that early recognition and immediate discontinuation of the offending agent remain the cornerstone of management. I commend the author for emphasizing patient education regarding skin hydration and sun protection during the desquamation phase. These simple, low-cost interventions significantly improve quality of life during recovery. Let us not underestimate the power of basic dermatological care.

Arjun Deva

December 12, 2025 AT 21:02Wait… so the government lets drug companies sell antibiotics that can turn your skin into a pustule factory… and they don’t test for the HLA-B*59:01 gene first? This is a cover-up. Big Pharma knows this happens and hides it. They don’t want you to know you could die from a simple sinus infection pill. And why is secukinumab only being tested now? Because they’re waiting for more people to get sick…

Mayur Panchamia

December 14, 2025 AT 14:45India has been treating these rashes with turmeric and neem for centuries. Why are we listening to Western doctors with their fancy biologics? We don’t need $10,000 shots. We have Ayurveda. This article reads like a pharmaceutical ad. AGEP? More like AGED-American Grown Exaggerated Disease.

Karen Mitchell

December 15, 2025 AT 18:45It is deeply irresponsible to suggest that steroids may be beneficial in severe cases. The risks of immunosuppression, hyperglycemia, and opportunistic infection far outweigh the marginal benefit of a 4-day reduction in recovery time. This article dangerously blurs the line between evidence-based medicine and anecdotal optimism. The American Journal of Clinical Dermatology’s ‘individualized’ approach is a euphemism for medical malpractice.

Geraldine Trainer-Cooper

December 17, 2025 AT 07:27so like… the whole thing is just your body being like ‘nope not today’ and then you stop the pill and it’s over? why do we need all this science. just don’t take the pill if you’re scared. also i think my dog had this once.

Kenny Pakade

December 18, 2025 AT 22:20Why is this even an issue? Americans are allergic to everything. Take a pill? Get a rash? Big deal. We don’t have time for this. We have real problems. Also, why is everyone so obsessed with biologics? Just go to a real doctor, not some skin specialist with a PhD in fancy words.

Brooke Evers

December 20, 2025 AT 18:26I just want to say how incredibly important it is that we normalize the experience of sudden, terrifying skin reactions. I had AGEP after a course of azithromycin, and no one told me the peeling was normal-I thought I was dying. I spent days crying in the shower because my skin felt like it was cracking open. The moisturizers with ceramides? Life-changing. And the fact that this article mentions not scratching? I wish I’d known that sooner. Please, if you’re reading this and you’ve ever had a weird rash after a pill-you’re not alone. And you didn’t do anything wrong. Your body just got confused. And now we know how to help it.

Saketh Sai Rachapudi

December 22, 2025 AT 09:41HLA-B*59:01? I think you mean HLA-B59:01. You forgot the colon. And also, this article ignores that Indian patients rarely get AGEP because we don’t take antibiotics like candy. You Americans overprescribe everything. We have discipline. You have panic.

Nigel ntini

December 24, 2025 AT 07:19This is one of the clearest, most compassionate explanations of AGEP I’ve ever read. The balance between scientific detail and human experience is perfect. I’m sharing this with my nursing students. The point about documenting triggers in charts? So critical. So many patients get re-exposed because the system fails them. Thank you for writing this. We need more like it.