How Peer Attitudes Shape Everyday Choices Through Social Influence

Have you ever bought a hoodie because everyone else was wearing it? Or switched to a new phone just because your friends raved about it? You weren’t alone. These aren’t random decisions-they’re the quiet result of something psychologists call social influence. It’s not about being weak or easily swayed. It’s about how deeply our brains are wired to sync up with the people around us. And it’s happening every day, in ways we rarely notice.

Why We Copy Without Realizing It

Your brain doesn’t treat peer opinions like background noise. It treats them like data. When you’re unsure what to do-whether it’s choosing a snack, picking a movie, or deciding whether to try vaping-your brain automatically checks what others are doing. This isn’t laziness. It’s efficiency. In 1955, Solomon Asch ran a famous experiment where people were asked to match line lengths. When everyone else in the room gave the wrong answer, 76% of participants went along with them-even when the right answer was obvious. That’s not about stupidity. It’s about the brain’s need for social alignment. Modern fMRI scans show why. When people conform, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum light up like a Christmas tree. These are the same areas that activate when you taste something delicious or get paid. In other words, going along with the group doesn’t feel like surrendering. It feels like winning.The Two Hidden Needs Driving Conformity

Not all peer pressure is the same. Research from 2022 found that two core needs drive most conformity: being liked and belonging. Together, they explain over 64% of why people change their choices to match their peers. If you’re a teenager, and everyone in your group talks about a new energy drink, you might not even like the taste. But if saying no means you’re labeled "weird," your brain calculates the cost. That’s the "being liked" part. The "belonging" part is deeper. It’s not just about fitting in-it’s about feeling safe. Humans evolved in tribes. Being cast out wasn’t just embarrassing-it was deadly. So your brain still treats social exclusion like a physical threat. This is why interventions that work best don’t just tell kids "don’t vape." They create peer-led groups where the norm shifts. The CDC’s "Friends for Life" program cut adolescent vaping by 18.7% by training popular, respected students to model healthy choices. Not because they were perfect. But because they were trusted.Status Matters More Than You Think

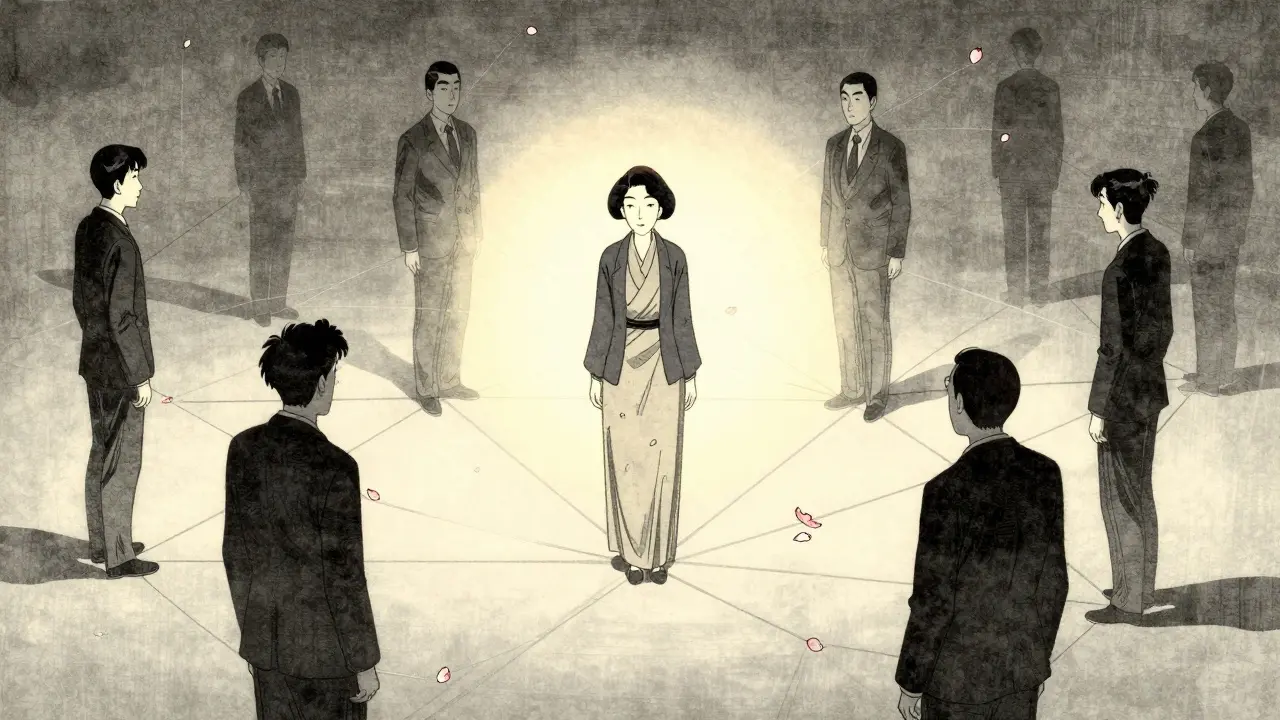

Not all peers are created equal. Influence doesn’t come from just anyone. It comes from those with social status. A 2015 study found that when teens saw someone they considered "popular" act responsibly, their own prosocial behavior jumped by 37.8%. But when the same behavior came from someone with average status, the boost was only 18.2%. And here’s the twist: the strongest influence doesn’t come from the most popular person. It comes from someone just a little bit above you. Too much distance creates intimidation. Too little creates no incentive. The sweet spot? A status gap of 0.4 to 0.6 standard deviations. That’s the person who’s liked, respected, and still feels reachable. This is why peer influence campaigns fail when they pick the wrong leaders. Targeting the absolute top of the social ladder often backfires. It feels unattainable. But picking someone who’s just a step ahead? That’s contagious.

Networks, Not Just Individuals

Social influence doesn’t flow like water from one person to another. It moves through networks. Think of your friends as a web. If you’re connected to three people who all vape, your odds of vaping go up-even if you don’t talk to them directly. That’s because you absorb the group’s norms. Studies show that influence probability increases by 47% for every additional connection you have to someone who’s adopted a behavior. But only if the relationship is strong. Weak ties-casual acquaintances-barely move the needle. Real influence lives in tight-knit groups where people spend time together, share secrets, and know each other’s routines. This is why school-wide anti-vaping campaigns often flop. If the peer network is fragmented, or if the kids who vape are clustered in separate cliques, flooding the whole school with posters won’t change anything. But if you identify the densest clusters-the groups where everyone knows everyone-and train a few trusted members in each to speak up? That’s when change sticks.The Dark Side: When Influence Goes Wrong

Social influence isn’t always good. It can push people toward risky behaviors too. Longitudinal studies tracking 1,245 Dutch teens over two years found that peer attitudes directly increased depressive symptoms by 37% in those who were already vulnerable. But here’s the catch: it wasn’t just direct influence. It was deselection. Teens who didn’t match the group’s mood or habits were quietly pushed out. They left the group. They stopped being invited. Over time, isolation made their depression worse. This is why simply telling teens "don’t be like them" doesn’t work. It ignores the social mechanics. The real problem isn’t the behavior-it’s the system that rewards conformity and punishes difference. Even worse, people often misread what’s normal. A 2014 study found that 67% of teens overestimated how much their peers drank, smoked, or used drugs by at least 20%. That’s called pluralistic ignorance. Everyone thinks everyone else is doing it, so they do it too-even if most people aren’t.

How to Use This Knowledge-Responsibly

This isn’t just theory. It’s being used in real programs-with results. - The "Be Real. Be Ready." campaign boosted teen emergency preparedness by 29.4% by having peers model checking smoke alarms and building kits-not by lecturing. - Facebook reduced harmful content sharing by 19.3% by boosting posts from users who regularly shared positive, supportive content. - Schools using peer leaders in anti-bullying programs saw a 31% drop in incidents over one year. The key? Don’t target the crowd. Target the connectors. Train the quiet kids who are respected. Let them lead. Give them tools, not scripts. And never assume the problem is ignorance. Often, the problem is misperception.What This Means for You

If you’re a parent, teacher, or just someone trying to make a difference: stop yelling. Start observing. Who are the quiet influencers in your circle? Who gets listened to? Who’s not loud, but whose opinion matters? If you’re trying to change your own habits, ask: "Who do I want to be like?" Not who I’m told to be like. Who I actually admire. Then spend more time with them. Not to copy them. But to let their habits rub off on you. Social influence isn’t manipulation. It’s human nature. And once you understand how it works, you can use it-not to control others, but to build better groups. Ones where the right choices feel natural. Where belonging doesn’t mean losing yourself. Where being yourself is the most popular thing of all.Why do people conform even when they know they’re wrong?

People conform because the brain treats social approval like a reward. Studies using fMRI show that going along with the group activates the same areas of the brain that respond to food, money, or praise. Even when someone knows the answer is wrong, the fear of standing out triggers stress responses. The discomfort of being different often outweighs the discomfort of being wrong.

Can social influence be positive?

Absolutely. Peer influence drives healthier eating, better study habits, and increased volunteering. Programs that train respected peers to model positive behaviors-like quitting vaping or checking smoke alarms-see success rates 30% higher than traditional education campaigns. The key is making the desired behavior feel normal, not forced.

Are some people more easily influenced than others?

Yes. Susceptibility varies based on age, self-esteem, and social context. Adolescents are most vulnerable, especially between ages 12 and 16. People with low self-esteem or weak social support are also more likely to conform. But even adults aren’t immune-especially in unfamiliar situations or when they’re unsure of the right choice.

How does social media change peer influence?

Social media amplifies influence by making peer behavior visible 24/7. You don’t need to be in the same room to feel pressure. But it also distorts reality. People post highlights, not struggles, leading to inflated perceptions of what’s normal. This can create false norms-like thinking everyone is richer, happier, or more active than they really are. Algorithms make this worse by showing you content that matches your group’s views, reinforcing echo chambers.

Can you reduce negative peer influence?

Yes, by shifting the group norm. Instead of fighting bad behavior, introduce a better one through trusted peers. Correct misperceptions-like showing teens that most of their classmates don’t vape. Build environments where standing out for good reasons is rewarded, not punished. And give people space to say no without losing their social standing.

Is peer influence stronger than family influence?

For teens and young adults, yes-especially in areas like fashion, music, slang, and social habits. Family shapes core values, but peers shape daily choices. That’s because peers are the immediate social environment. Parents may say "don’t drink," but if your friends are all drinking and you’re the only one not, the pressure becomes real. The shift happens around age 12, when peer approval starts outweighing parental approval in many social contexts.

Harriot Rockey

February 2, 2026 AT 12:18OMG YES this is so real 😭 I used to think I was weird for buying the same snacks as my friends... turns out my brain was just doing its job! So glad someone finally put this in terms I can feel, not just study. 🙌

Geri Rogers

February 4, 2026 AT 07:26Stop acting like this is new info. We’ve known this since the 90s. The real win here is how schools are finally using peer leaders instead of boring assemblies. That’s the only thing that works. No more lectures. Just let the cool kids say ‘hey, don’t vape’ and watch it spread. 🙏

Samuel Bradway

February 5, 2026 AT 08:03I’ve seen this in my own life. I started biking to work because my roommate did it. Not because I cared about the environment-just because it felt normal. Then I started noticing how much better I felt. Weird how you don’t realize you’re being influenced until you look back.

rahulkumar maurya

February 6, 2026 AT 10:37How quaint. You cite Asch and fMRI like these are revelations. The Vedas described social conformity over 3,000 years ago as ‘samaja samskara’-the collective conditioning of the mind. Modern neuroscience merely confirms what ancient sages observed in meditation. Your paper is a footnote to millennia of wisdom.

pradnya paramita

February 7, 2026 AT 16:03From a behavioral economics standpoint, this is classic normative social influence with a side of informational cascades. The ventromedial PFC activation correlates with reward prediction error minimization. Status-based influence operates under a bounded rationality model where heuristics replace utility maximization. TL;DR: people follow the path of least cognitive resistance when uncertainty is high.

Amit Jain

February 8, 2026 AT 07:29Simple truth: if your friends are doing it, you’ll do it too. No science needed. I grew up in a village where everyone drank chai at 5am. I didn’t like it at first. Now I can’t start my day without it. That’s all.

Keith Harris

February 9, 2026 AT 10:12Oh wow, so we’re all just sheep? Big shocker. Let me guess-next you’ll tell me water is wet and gravity exists. Meanwhile, I’m over here buying the *opposite* of everything because I’m not a mindless drone. Your whole post is just a fancy way of saying ‘conformity is real.’ Congrats, you discovered the wheel. Again.

Kunal Kaushik

February 10, 2026 AT 15:06Been thinking about this a lot lately. I used to avoid speaking up in meetings because everyone else seemed so confident. Then I realized half of them were just faking it. The real influencers? The quiet ones who nod and say ‘yeah, let’s try that’-and then everyone follows. Not the loudest. Not the most popular. Just the ones who feel safe to follow.

Alec Stewart Stewart

February 12, 2026 AT 07:45This is why I stopped trying to ‘fix’ my niece’s fashion choices. She wears those neon socks because her friend does-and her friend wears them because *her* friend does. It’s not about the socks. It’s about belonging. Let her have the socks. Let her find her people. The rest will come.

Roshan Gudhe

February 13, 2026 AT 10:12What if conformity isn’t the problem? What if it’s the only thing that keeps civilization from collapsing into chaos? We don’t need more rebels-we need more anchors. The quiet ones who hold the group together without demanding applause. Maybe the real revolution isn’t in rejecting the group… but in becoming the kind of person others want to follow.

Rachel Kipps

February 14, 2026 AT 18:10i read this and i just... i dont know. i think its true but also i feel like i dont belong in any group anymore. maybe thats why i dont do anything anymore. sorry for the typos. tired.

Jamillah Rodriguez

February 15, 2026 AT 07:16Okay but like... why is this even a thing? Who cares? I just want to watch Netflix and not think about how my brain is being hacked by my high school clique from 2017. 😴

Nathan King

February 15, 2026 AT 11:27While the empirical underpinnings of social influence are indeed robust, the author’s conflation of neurobiological reward pathways with moral agency is methodologically suspect. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex does not confer ethical validity to conformity-it merely registers reinforcement. To frame this as ‘human nature’ is to commit the naturalistic fallacy. One may observe conformity; one cannot thereby justify its normative superiority. The real ethical imperative lies not in leveraging influence, but in cultivating critical autonomy-a concept conspicuously absent from this otherwise compelling narrative.

Demetria Morris

February 17, 2026 AT 06:42I used to think I was the only one who felt guilty for liking things just because my friends liked them. Like, I don’t even like coffee, but I bought a $7 latte every morning because everyone else did. Then I realized: I wasn’t buying coffee. I was buying permission to belong. And that’s the saddest thing of all.