Metformin and Alcohol: Understanding the Lactic Acidosis Risk

Metformin and Alcohol Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

This tool helps you understand your risk level when combining metformin with alcohol. Based on your responses to the questions below, it will provide you with a risk assessment and guidance on safe practices.

Your Risk Assessment

Important Warning

Even moderate drinking with metformin can be dangerous for some people. Never ignore symptoms like muscle pain, trouble breathing, or rapid heartbeat.

- Stop drinking if you're at high risk

- Monitor for symptoms listed below

- Always eat when drinking alcohol

- Consult your doctor for personalized advice

Emergency symptoms

Go to ER immediately if you experience:

- Deep, rapid breathing

- Unusual muscle pain or weakness

- Severe nausea or vomiting

- Cold or blue skin

- Rapid heartbeat

Combining metformin and alcohol might seem harmless-after all, many people with type 2 diabetes enjoy an occasional drink. But beneath that casual habit lies a rare, silent danger: lactic acidosis. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does, it can kill within hours. And unlike most drug interactions, this one doesn’t just make you feel sick-it disrupts your body’s entire acid-base balance, turning your blood acidic and shutting down vital organs.

What Is Lactic Acidosis?

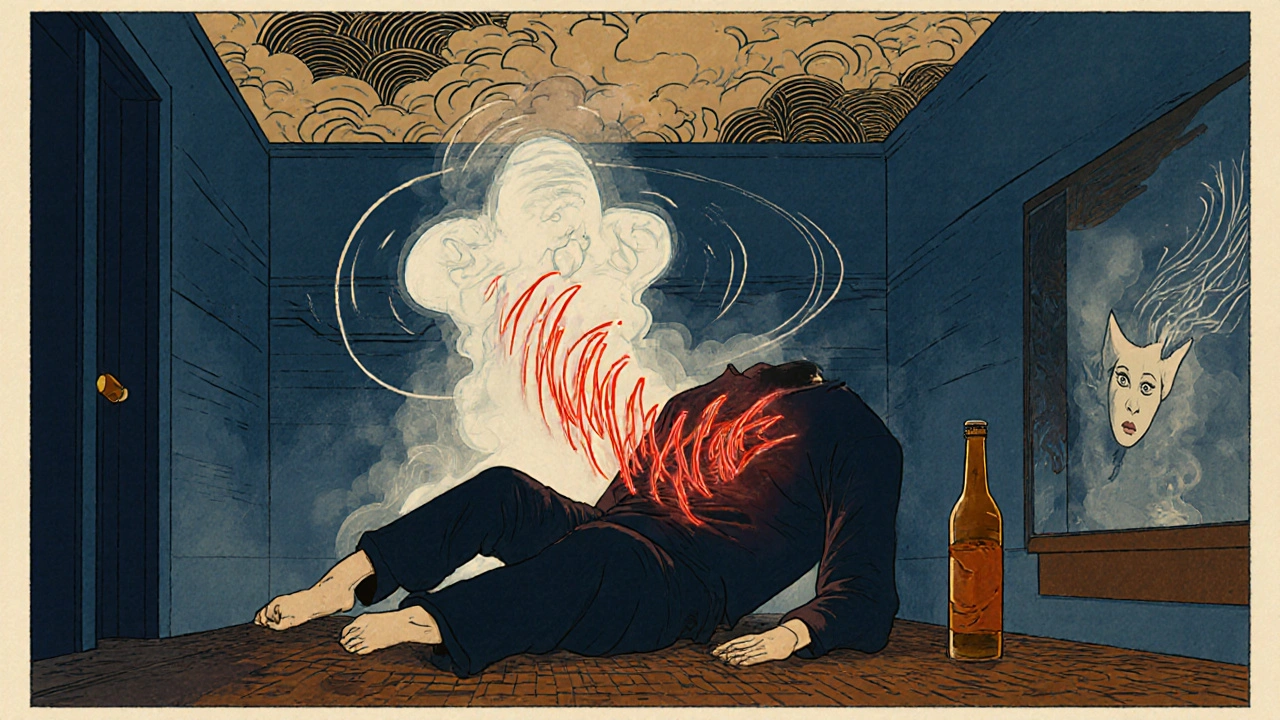

Lactic acidosis isn’t just high lactate levels. It’s when your blood pH drops below 7.35 because too much lactic acid builds up and your body can’t clear it. Normal lactate levels are under 2 mmol/L. In lactic acidosis, they spike past 5 mmol/L. That’s not a lab curiosity-it’s a medical emergency. Symptoms include deep, rapid breathing (your body trying to blow off acid), muscle cramps, nausea, vomiting, cold extremities, and a racing heart. Many people mistake these for a bad hangover. That’s the problem.

Metformin contributes to this because it reduces the liver’s ability to convert lactate back into glucose. Alcohol makes it worse. When you drink, your liver prioritizes breaking down ethanol. To do that, it uses up NAD+, a molecule needed to process lactate. So while metformin slows lactate removal, alcohol blocks the backup system. Together, they create a bottleneck your body can’t handle.

How Common Is It?

The numbers are small, but they’re terrifying. Studies estimate about 0.03 cases of metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) per 1,000 patient-years. That’s roughly 3 cases in 10,000 people taking metformin over a year. Fatal cases? About 0.015 per 1,000. So, less than 2 deaths per 100,000 users annually.

Compare that to phenformin, metformin’s predecessor, which caused 40-64 fatal cases per 100,000 patient-years. That’s why phenformin was pulled from the market in 1978. Metformin is 100 times safer-but it’s not risk-free. And alcohol pushes that risk up, even in people with normal kidney function.

There are documented cases of people with no kidney disease developing lactic acidosis after binge drinking while on metformin. One 65-year-old man in a 2024 case report had a blood lactate level of 6.2 mmol/L after consuming six beers over two days. He didn’t have diabetes complications. He didn’t have liver disease. He just drank too much while taking his daily pill. He ended up in the ICU.

The FDA’s Black Box Warning

The FDA doesn’t issue black box warnings lightly. It’s the strongest possible alert. And metformin has one-for lactic acidosis. The label says: “Warn against excessive alcohol intake.” That’s it. No definition of “excessive.” No safe number of drinks. No exceptions.

Why? Because there’s no clear threshold. One glass of wine? Maybe fine for someone with healthy kidneys and no other risk factors. Ten shots at a party? Dangerous. A few beers every weekend? Possibly risky over time. The science doesn’t give us a line in the sand. So the warning stays vague-because the risk isn’t linear. It’s unpredictable.

Some doctors tell patients to avoid alcohol entirely. Others say one drink a day is okay. But even the American Diabetes Association’s 2023 guidelines only say “excessive alcohol consumption should be avoided.” They don’t define excessive. That’s not a loophole-it’s a gap in the evidence.

Real People, Real Consequences

Online forums are full of stories that don’t make it into medical journals. One Reddit user, ‘SugarFreeLife,’ described muscle locking and trouble breathing after 10 shots at a bachelor party. His lactate level was 6.1 mmol/L. He didn’t know what was happening until his friend called 911.

On Healthline’s diabetes forum, ‘DiabetesWarrior42’ had muscle cramps and nausea after six beers. He went to the ER thinking it was food poisoning. His lactate was 6.2 mmol/L. He spent three days in the hospital. He hasn’t had a drink since.

GoodRx surveyed over 1,200 metformin users. Nearly 8 out of 10 cut back on alcohol because of lactic acidosis fears. Over 40% named it as their top concern-higher than weight gain, diarrhea, or B12 deficiency.

And here’s the quiet danger: 68% of people who ended up in the hospital with MALA didn’t recognize their symptoms as serious. They thought it was a hangover. Or a stomach bug. Or stress. By the time they sought help, their blood was too acidic to recover easily.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

It’s not just about drinking. It’s about context.

- Chronic heavy drinkers-daily consumption over weeks or months-have chronically impaired liver function. Their lactate clearance is already down.

- Binge drinkers-4+ drinks for women, 5+ for men in 2 hours-overwhelm the liver’s ability to process ethanol and lactate at the same time.

- People with kidney issues-since 90% of metformin leaves the body through the kidneys, even mild kidney decline increases drug buildup.

- Older adults-liver and kidney function naturally decline after 60, making clearance slower.

- Those with liver disease, heart failure, or recent surgery-these conditions reduce tissue oxygen delivery, which increases lactate production.

Even if you’re young and healthy, a single night of heavy drinking while on metformin can be enough. The risk isn’t just cumulative-it can be acute.

What About Moderate Drinking?

Some doctors say one drink a day is fine. The American Heart Association defines moderate drinking as up to one drink per day for women, two for men. But here’s the catch: no clinical trial has proven this is safe for metformin users.

Dr. Robert A. Rizza from Mayo Clinic says moderate drinking “may be acceptable” for some-with normal kidneys and no other risks. But he adds: “Any pattern of binge drinking or chronic heavy use creates a potentially dangerous situation.”

So if you’re thinking, “I’ll just have one glass of wine,” ask yourself: Are you sure your kidneys are working perfectly? Are you sure you won’t drink more later? Are you sure you won’t get sick, dehydrated, or skip a meal? One variable changes, and the risk changes with it.

The safest answer? Avoid alcohol during the first 4-8 weeks of starting metformin. Your body is adjusting. Then, if you choose to drink, do it rarely, never on an empty stomach, and never in large amounts.

Other Risks You Might Not Know

Metformin and alcohol don’t just risk lactic acidosis. They team up to drain your vitamin B12.

Studies show 7-10% of long-term metformin users develop B12 deficiency each year. Alcohol makes it worse. Both interfere with absorption in the gut. Low B12 means fatigue, memory problems, nerve damage, and even anemia. It’s slow, silent, and reversible-if caught early. But if you’re drinking regularly and on metformin, you’re at double risk.

Doctors should check B12 levels every 1-2 years in people on metformin. If you drink, ask for it sooner.

What Should You Do?

Here’s what actually works:

- Don’t drink during the first 2 months of starting metformin. Your body needs time to adjust.

- Avoid binge drinking at all costs. Four or more drinks in two hours? That’s a red flag.

- Never drink on an empty stomach. Alcohol + metformin can also cause low blood sugar. Food slows both absorption and risk.

- Know the warning signs: Unusual muscle pain, trouble breathing, stomach pain, dizziness, cold skin, rapid heartbeat. If you feel this way after drinking, go to the ER. Don’t wait.

- Ask your doctor for a kidney function test at least once a year. If your eGFR drops below 45, talk about alternatives.

- Consider alternatives if you drink regularly. GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide or SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin don’t carry lactic acidosis risk. They’re more expensive, but they’re safer if alcohol is part of your life.

The Bigger Picture

Metformin is still the most prescribed diabetes drug in the world-over 150 million prescriptions a year in the U.S. alone. It’s cheap, effective, and helps with weight and heart health. It’s not going away.

But the lactic acidosis risk, especially with alcohol, is real. It’s not hype. It’s not fearmongering. It’s biology. And while newer drugs are rising, none of them eliminate the need for caution.

The FDA, EMA, and ADA all agree: avoid excessive alcohol. But they don’t define excessive. That’s on you. Your body. Your choices.

Metformin saved millions from complications. But it can’t save you if you ignore the warning signs. Alcohol doesn’t just dull your senses-it dulls your body’s ability to protect itself. And when it teams up with metformin, the consequences can be irreversible.

If you’re on metformin and you drink, don’t assume you’re safe. Assume you’re at risk-and act like it.

Can I have one glass of wine with dinner while taking metformin?

Some people with healthy kidneys and no other risk factors may tolerate one glass of wine occasionally. But there’s no proven safe level. The FDA doesn’t define “moderate” for metformin users. If you choose to drink, do it rarely, never on an empty stomach, and never if you feel unwell. Always monitor for symptoms like muscle pain or trouble breathing.

Is lactic acidosis the same as ketoacidosis?

No. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) happens when your body burns fat for fuel because it lacks insulin, producing ketones. Lactic acidosis is caused by too much lactic acid, often from impaired liver or kidney function. Metformin and alcohol cause lactic acidosis, not DKA. They’re different conditions with different treatments.

Does alcohol make metformin less effective?

Alcohol doesn’t directly reduce metformin’s ability to lower blood sugar. But it can cause unpredictable drops in glucose, especially if you drink without eating. This increases hypoglycemia risk, which can be dangerous on its own. The bigger danger is lactic acidosis, not reduced effectiveness.

What are the signs I should go to the ER?

If you’re on metformin and drink alcohol, go to the ER immediately if you experience: deep, rapid breathing; unusual muscle pain or weakness; severe nausea or vomiting; dizziness or lightheadedness; cold or blue skin; or a rapid heartbeat. These are signs your blood is becoming too acidic. Delaying care can be fatal.

Are there safer diabetes medications if I drink regularly?

Yes. GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) and SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin (Jardiance) don’t carry a lactic acidosis risk. They’re more expensive and may cause gastrointestinal side effects or urinary tract infections, but they’re safer if you drink alcohol regularly. Talk to your doctor about switching if alcohol is a regular part of your life.

Jenny Lee

November 17, 2025 AT 20:45One glass of wine with dinner? I do it. No issues. But I also get my kidney numbers checked yearly and never drink on an empty stomach.

Joshua Casella

November 19, 2025 AT 08:09Metformin isn't the villain here. Alcohol is. The liver doesn't care if you're diabetic or not-it's just trying to process ethanol. When you stack that with metformin, you're asking your body to run two systems at once with one engine. It's not complicated biology. It's just poor choices masked as moderation.

I've seen people treat this like it's a game: 'Oh, I had one drink last week, it's fine.' But one drink becomes two, then three, then a weekend binge. And then you're in the ICU wondering why your legs feel like concrete.

The FDA warning is vague because the risk isn't linear. It's exponential. One drink? Maybe safe. Ten drinks in 24 hours? That's a death sentence waiting to happen. No amount of 'but my kidneys are fine' changes that.

And let's not pretend this is about willpower. It's about biological limits. Your body doesn't negotiate. It doesn't care if you're 'responsible.' It just shuts down when the acid hits 5 mmol/L.

If you're on metformin and you drink, you're not 'managing your condition.' You're playing Russian roulette with your acid-base balance. And the gun has one bullet. It doesn't matter how many times you pull the trigger before it fires. One pull is enough.

Stop romanticizing 'moderation.' Moderation is for people who don't have a ticking clock in their bloodstream.

Alex Boozan

November 20, 2025 AT 20:07Let’s be clear: the pharmacokinetic interaction is textbook. Metformin inhibits mitochondrial complex I → reduced oxidative phosphorylation → increased NADH/NAD+ ratio → lactate accumulation. Alcohol metabolism via ADH further depletes NAD+, exacerbating the redox shift. Hepatic gluconeogenesis is impaired, lactate clearance plummets, and voilà-lactic acidosis. This isn’t speculation. It’s biochemistry 101.

The real issue? Medical education. Most clinicians don’t emphasize this because they assume patients won’t drink. But the data shows otherwise. Over 40% of metformin users consume alcohol regularly. The disconnect between clinical guidelines and real-world behavior is staggering.

And don’t get me started on the 'one drink is fine' myth. That’s not evidence-based. That’s wishful thinking dressed in white coats. No RCT has established a safe threshold. Zero. Nada. Not even for healthy young adults.

The only responsible stance? Absolute abstinence. If you can’t do that, switch to an SGLT2 inhibitor. The cost is higher, but so is your survival probability.

mithun mohanta

November 21, 2025 AT 01:10OMG, I just read this and my soul is shaking. I mean, like, I’ve been on metformin for 3 years and I’ve had 3 glasses of wine at my cousin’s wedding, and I thought I was being sooo responsible!! But now I’m like… what if my liver is already screaming and I just ignored it??

And then there’s this whole thing about B12 deficiency?? I’ve been tired for months and thought it was just ‘adulting’… but what if it’s metformin + wine??

I’m going to the doctor tomorrow. I’m getting a B12 test. I’m getting an eGFR. I’m throwing out my wine glass. I’m becoming a new person. #MetforminWakeUpCall

Ram tech

November 23, 2025 AT 00:20people just dont care about their health anymore. you take a pill, you drink, you think its fine. then you die. its sad. i dont even know why doctors still prescribe this. just give them insulin and be done with it.

Kevin Jones

November 24, 2025 AT 13:55Here’s the uncomfortable truth: this isn’t about alcohol. It’s about control. We want to believe we can compartmentalize risk-that one glass won’t matter, that our body is ‘strong enough.’ But biology doesn’t care about our narratives. It only responds to chemistry.

The real tragedy isn’t the lactic acidosis. It’s the normalization of self-destruction under the banner of ‘moderation.’ We’ve turned medical warnings into social loopholes. ‘I’m not binge drinking-I’m just having a glass with dinner.’

That’s not moderation. That’s denial with a wine cork.

And we wonder why chronic disease is exploding.

Erica Lundy

November 24, 2025 AT 23:22The philosophical dilemma here is not merely pharmacological, but existential: when a medical intervention, designed to preserve life, becomes a vector for its potential termination through the very agency we exercise to enjoy it-what does that say about the nature of autonomy in the age of pharmacological dependency?

Metformin, in its efficacy, grants us the illusion of control over metabolic chaos. Yet alcohol, in its cultural sanctity, demands we surrender to pleasure without consequence. The collision of these two imperatives-health and hedonism-reveals a deeper fracture in how we reconcile bodily integrity with personal freedom.

The FDA’s vagueness is not negligence; it is an admission that no quantitative threshold can capture the qualitative weight of individual choice. The warning is not for the body-it is for the soul.

And yet, we continue to measure safety in drinks per week, rather than in the quiet, accumulating erosion of metabolic resilience.

Perhaps the real question is not whether we should drink, but whether we are willing to bear the full moral weight of our biological compromises.

Richard Couron

November 25, 2025 AT 01:47you think this is about alcohol? nah. this is a big pharma scam. metformin was never meant to be long-term. they knew it caused acidosis but kept selling it because insulin is way more profitable. and now they want you to switch to ozempic? that's a $1000/month racket. they want you dependent on expensive drugs while pretending metformin is 'safe' if you don't drink. but if you do drink? oh no, you're a bad patient. it's not the drug, it's you. classic.

the real danger? they don't test this properly. they just say 'rare' and move on. how many people died in the 90s and got buried as 'alcohol poisoning' when it was actually MALA? nobody knows. because they don't autopsy anymore. they just write 'natural causes' and call it a day.

don't trust the system. they're not protecting you. they're protecting profits.

Premanka Goswami

November 27, 2025 AT 01:01Think about it: if your liver is a factory, metformin is a broken conveyor belt, and alcohol is a fire in the warehouse. Now imagine the safety inspector says, 'Just don't light the fire.' But the fire is everywhere. It's called Friday night. It's called birthday parties. It's called stress relief. The system doesn't give you a real choice. It gives you guilt. And that's the real poison.

They say 'avoid excessive alcohol.' But who defines excessive? The FDA? The ADA? Your doctor who doesn't even ask? You're left alone in the dark with a pill bottle and a glass, wondering if you're a monster for wanting to feel normal.

Maybe the answer isn't more warnings. Maybe it's more compassion. And maybe, just maybe, we need drugs that don't force us to choose between survival and being human.

Joshua Casella

November 27, 2025 AT 17:22Kevin Jones nailed it. This isn't about alcohol. It's about the illusion of control. We treat medical advice like a menu: 'I'll have the metformin, hold the abstinence.' But biology doesn't do à la carte.

And Erica Lundy? You're right. The real tragedy isn't lactic acidosis-it's that we've turned medical risk into a moral test. If you drink, you're irresponsible. If you don't, you're a saint. But what about the people who just want to feel human for one night? They're not villains. They're just trapped.

Maybe the solution isn't more warnings. Maybe it's better drugs. And maybe, just maybe, we need to stop shaming people for wanting to live-not just survive.