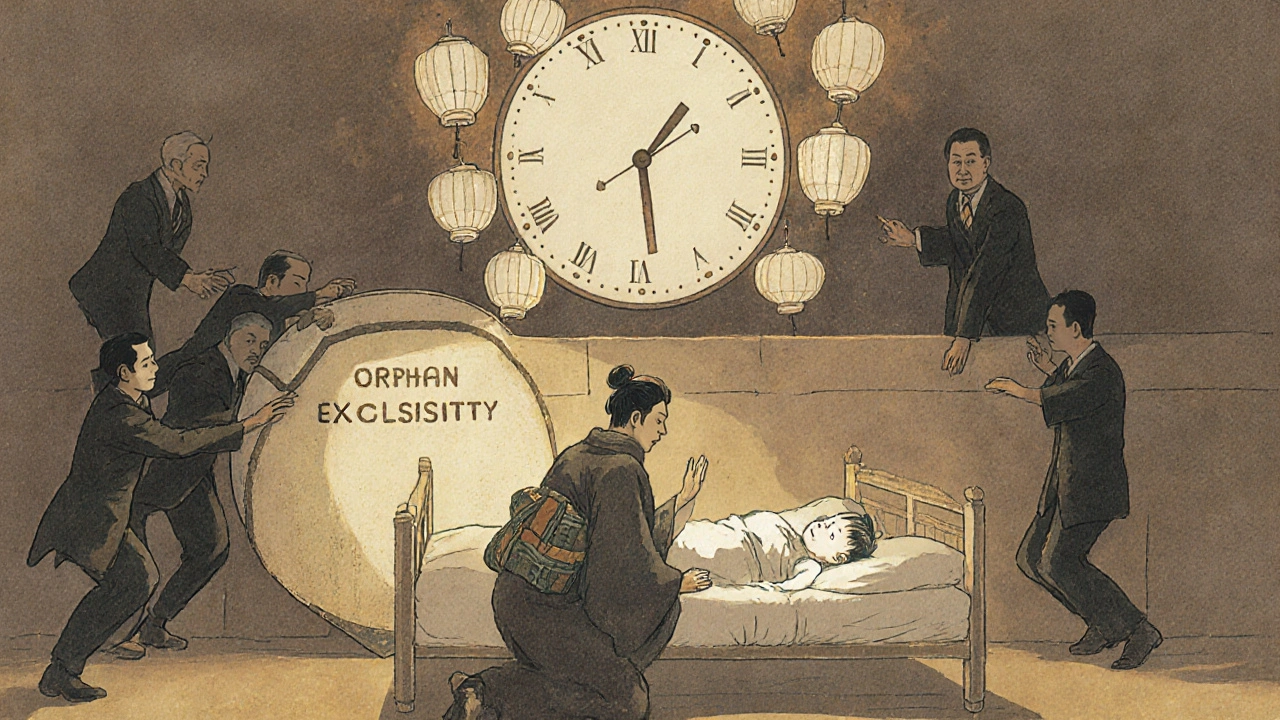

Orphan Drug Exclusivity: How Rare-Disease Medicines Get Market Protection

Before 1983, fewer than 10 treatments existed for rare diseases in the U.S. Today, over 1,000 are approved. What changed? The orphan drug exclusivity system. It didn’t just encourage drug development-it created a new economic reality for diseases that once had no hope of a medicine.

What Exactly Is Orphan Drug Exclusivity?

Orphan drug exclusivity is a seven-year period of market protection granted by the FDA to a drug approved for a rare disease. It doesn’t mean the drug is patented. It means no other company can get FDA approval to sell the same drug for the same rare condition during that time-unless they prove their version is clinically superior. The law behind it, the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, was simple: if a disease affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S., and developing a treatment won’t pay for itself, the government steps in. It gives companies a guaranteed window to recoup costs without immediate competition. This isn’t a subsidy. It’s a market shield. The exclusivity starts on the day the FDA approves the drug for marketing, not when the patent is filed. That’s critical. Many orphan drugs have patents that expire before the seven-year exclusivity ends. For those, the exclusivity is the real barrier to generics.How It Works: The Horse Race for Approval

Here’s the twist: multiple companies can apply for orphan designation on the same drug for the same disease. But only the first to get FDA approval wins the exclusivity. Think of it like a race where everyone lines up at the starting line with the same car, but only the first across the finish line gets the prize. In 2021, two companies were racing to be first with a drug for a rare form of muscular dystrophy. One filed their application six months earlier. They got approved first. The other, even with identical chemistry, couldn’t enter the market for seven years-even though their clinical trial data was just as strong. This isn’t just theory. Since 1983, there have been over 6,500 orphan designations granted. But only about 1,085 have led to approved drugs. That’s because many companies start the race, but only a few finish.What It Protects-and What It Doesn’t

Orphan exclusivity is narrow. It protects only the combination of the specific drug molecule and the specific rare disease indication. That’s called the “dyad.” If a drug is approved for two conditions-one rare, one common-the exclusivity applies only to the rare one. For example, a drug approved for a rare nerve disorder can still be prescribed off-label for a common condition. And if a generic company wants to make that same drug for the common condition, they can. The orphan exclusivity doesn’t block them. This creates a loophole some companies exploit. A drug like Humira, which treats rheumatoid arthritis (a common condition), received orphan designation for several rare autoimmune diseases. That gave it extra exclusivity on those rare uses-even though it was already a billion-dollar drug. Critics call it “salami slicing”: cutting up one drug into multiple orphan designations to extend market control.

How It Compares to Patents and Other Countries

Patents protect the chemical structure or how a drug is made. Orphan exclusivity protects the use. They’re different tools. Most drugs rely on patents first. But for rare diseases, patents often expire before the drug even hits the market. That’s why orphan exclusivity matters more here. According to IQVIA, in only 60 of the 503 orphan drugs approved by 2018 did exclusivity outlast patent protection. For the rest, patents were the main barrier to generics. But for the 60, exclusivity was the only thing keeping competitors out. Outside the U.S., the rules vary. The European Union gives ten years of exclusivity, with a possible two-year extension if the company tests the drug in children. The U.S. doesn’t offer extensions. The EU also allows exclusivity to be cut from ten to six years if the drug turns out to be wildly profitable. The U.S. has no such safety valve.Why Companies Chase It-Even for Drugs That Already Make Money

The financial stakes are high. Developing a rare disease drug can cost $150 million or more. With only a few thousand patients, the price per dose has to be sky-high to break even. That’s why a seven-year monopoly isn’t just helpful-it’s necessary. A senior regulatory affairs manager at a mid-sized biotech told a 2022 industry forum: “Without orphan exclusivity, we wouldn’t have invested $150 million in our drug for a disease affecting only 8,000 people.” But it’s not just small companies. Big pharma uses orphan status to extend the life of mature drugs. Between 2010 and 2020, nearly half of all orphan approvals were for drugs already on the market for other uses. The FDA approved Ruzurgi for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in 2019. The same molecule had been sold for years under a different brand for a different condition. The orphan designation gave it a fresh seven-year clock.

The Hidden Hurdle: Proving Clinical Superiority

If another company wants to bring a similar drug to market during the exclusivity window, they must prove their version is clinically superior. That’s not easy. The FDA defines this as offering a “substantial therapeutic improvement”-better survival rates, fewer side effects, easier dosing. Since 1983, only three companies have successfully met this standard. One made a version that could be taken orally instead of by injection. Another reduced the frequency of dosing from daily to weekly. A third cut serious side effects by half. That’s why most competitors don’t even try. The cost of proving superiority often exceeds the potential profit. So, the original drug stays alone on the market for the full seven years.Who Benefits-and Who Pays

Patients with rare diseases benefit most. Before 1983, many had no treatment options. Today, 78% of patient advocacy groups say orphan exclusivity is essential for getting new drugs developed, according to a 2022 survey by the National Organization for Rare Disorders. But there’s a cost. The same exclusivity that enables development also enables high prices. A single dose of some orphan drugs can cost over $100,000 a year. Forty-two percent of patient groups in that same survey expressed concern about affordability. The system works because it balances two goals: get treatments to patients who need them, and let companies make money doing it. But the balance is fragile. As more drugs get orphan status-and prices rise-pressure grows to reform the system.What’s Next for Orphan Drug Exclusivity?

The FDA approved 434 orphan designations in 2022-up from 127 in 2010. By 2027, Deloitte predicts 72% of all new drugs will have orphan status. That’s not because rare diseases are exploding. It’s because the financial incentive is too strong to ignore. The European Commission is now considering reducing its exclusivity period from ten to eight years for drugs that earn more than expected. The U.S. hasn’t moved yet, but the FDA issued new guidance in May 2023 to tighten the definition of “same drug” after controversies like Ruzurgi. Still, the system isn’t broken-it’s working exactly as designed. The question isn’t whether it should be removed. It’s whether it needs guardrails to prevent abuse. For now, orphan drug exclusivity remains the backbone of rare disease drug development. It turns a market that once ignored patients into one that now invests billions to help them. And for the 7 million Americans living with rare diseases, that’s not just policy-it’s life.How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts seven years, starting from the date the FDA approves the drug for marketing. This protection applies only to the specific drug and rare disease indication it was approved for. During this time, the FDA cannot approve another company’s version of the same drug for the same condition unless the new version demonstrates clinical superiority.

Can a drug have both a patent and orphan exclusivity?

Yes, most orphan drugs have both. Patents protect the chemical structure or manufacturing method, while orphan exclusivity protects the use of the drug for a specific rare disease. Patents often expire first, but orphan exclusivity can continue even after patent protection ends. In fact, for about 60 of the 503 orphan drugs approved by 2018, the seven-year exclusivity outlasted the patent.

What’s the difference between orphan designation and orphan approval?

Orphan designation is granted early in development when a drug is shown to target a rare disease affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. It gives access to tax credits, fee waivers, and protocol assistance-but no market protection. Orphan approval happens after the FDA reviews clinical data and grants marketing authorization. Only then does the seven-year exclusivity period begin.

Can generics enter the market after orphan exclusivity ends?

Yes. Once the seven-year exclusivity period ends, other companies can apply to market generic versions of the drug for the same rare disease. However, if the original drug is still under patent protection, generics still can’t enter until the patent expires. Many orphan drugs rely on patent protection even after exclusivity ends.

Why do some big pharma companies get orphan status for widely used drugs?

Some companies seek orphan designation for drugs already approved for common conditions, a practice sometimes called “salami slicing.” For example, Humira received orphan status for several rare autoimmune diseases despite being a top-selling drug for rheumatoid arthritis. This extends its market exclusivity beyond the original patent, delaying generic competition for those rare uses. While legal, it’s controversial because it can lead to higher prices without significantly expanding patient access.

Does orphan exclusivity apply outside the U.S.?

Yes, but the rules differ. The European Union grants ten years of market exclusivity for orphan drugs, with a possible two-year extension for pediatric studies. The EU can also reduce exclusivity to six years if a drug becomes highly profitable. The U.S. offers no extensions or reductions. Other countries have their own systems, but the U.S. and EU are the largest markets, and their rules heavily influence global development.

Peter Lubem Ause

November 30, 2025 AT 09:02Orphan drug exclusivity is one of those rare policies that actually works the way it was meant to. Before 1983, kids with rare diseases were basically left to fade away because no one could justify the cost. Now? We have treatments where there were none. It’s not perfect, but it’s the only thing keeping hope alive for families who’ve been told ‘there’s nothing we can do.’

And yes, some big pharma games the system with salami slicing - but that’s a loophole, not a flaw in the design. Fix the abuse, don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater.

linda wood

November 30, 2025 AT 12:33So let me get this straight - we’re giving a 7-year monopoly on a drug that costs $100k a dose… and we call it ‘compassionate capitalism’? 😒

Patients get medicine. Companies get to charge what they want. Taxpayers foot the bill. And if you dare ask why it’s so expensive, they say ‘but without exclusivity, we wouldn’t have invested!’

Fun fact: the same companies that cry poverty for rare diseases charge $200k/year for a drug that cost $15M to develop. I’m not mad… I’m just disappointed.

LINDA PUSPITASARI

December 1, 2025 AT 03:06As someone who’s worked in rare disease trials, I can tell you - this system saves lives. I’ve seen parents cry because their child got a drug that didn’t exist 5 years ago. The prices are insane, yes. But if you remove exclusivity, the pipeline dries up. No one will risk $150M on 8,000 patients.

Maybe we need price caps or reinsurance? But don’t kill the incentive. The real villains aren’t the biotechs - they’re the insurers who won’t cover it and the politicians who won’t fund patient assistance programs.

Also 🤞 for better pricing models soon. We’re working on it 💪

gerardo beaudoin

December 1, 2025 AT 09:52Just read this whole thing and honestly? I’m impressed. This isn’t some corporate scam - it’s a smart workaround for a market failure. If a disease affects fewer than 200k people, the free market ignores it. So the government says, ‘hey, here’s a shield while you build it.’

And yeah, Humira got orphan status for a rare form of lupus? Kinda sketchy. But that’s a case-by-case problem, not a system problem. We can fix the abuse without breaking the whole thing.

Joy Aniekwe

December 3, 2025 AT 01:13Oh wow, so the ‘orphan’ label is just a tax write-off with a side of monopoly? Brilliant. Let’s call it what it is: corporate welfare disguised as compassion.

Meanwhile, real orphans? Still waiting for food stamps.

Andrew Keh

December 4, 2025 AT 12:26I appreciate the nuance here. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s the only reason my nephew has a chance at walking. Before 1983, his condition had zero treatments. Now? He’s on a drug that only exists because this law exists.

Yes, the price is brutal. Yes, some companies abuse it. But the alternative - no drugs at all - is worse. We need reforms, not repeal.

Sullivan Lauer

December 5, 2025 AT 19:11Let me tell you something - I’ve been in this game for 20 years. I’ve seen companies go bankrupt trying to develop drugs for diseases that affect 300 people. I’ve sat in rooms with parents begging for anything, anything at all, that might give their child a year, a month, a day.

And then I’ve seen the same companies turn around and charge $500,000 a year for a pill that costs $2 to make - and I’ve seen the FDA say ‘we can’t touch it, it’s protected.’

So yes - this system created miracles. But it also created monsters.

It’s not that we don’t need exclusivity - it’s that we need limits. A cap on pricing. A sunset clause if profits exceed 500% ROI. A real definition of ‘clinically superior’ that doesn’t let them patent a different color capsule.

Because right now? We’re not saving lives. We’re selling hope at a markup.

And I’m tired of it.

Latika Gupta

December 6, 2025 AT 12:49Wait… so if a drug is approved for a common disease, but gets orphan status for a rare one, they can still sell it for the common one at regular price? But no one else can make the same drug for the rare one? That’s… kind of wild. So it’s like a legal loophole where you get monopoly power on a tiny slice of the market to protect the big slice? 😅