Postoperative Ileus and Opioids: How to Prevent and Treat Delayed Bowel Recovery After Surgery

Postoperative Ileus Risk Calculator

How Your Surgery Affects Bowel Recovery

Postoperative ileus (POI) is a common delay in gut function after surgery. This calculator estimates your risk based on surgery type, age, and opioid use.

What Is Postoperative Ileus-and Why Opioids Make It Worse

After surgery, your body should start moving again. But for many patients, the gut just stops. No gas. No bowel movement. No appetite. This isn’t normal recovery-it’s postoperative ileus (POI), a common and painful delay in gut function that can stretch hospital stays by days. And opioids, the go-to painkillers after surgery, are one of the biggest reasons why.

POI isn’t just discomfort. It’s a medical event. When your intestines go quiet for more than three days after surgery, it’s clinically significant. You might feel bloated, throw up, or be unable to drink even water. Doctors see it all the time-especially after abdominal, colorectal, or orthopedic surgeries. But here’s the catch: it’s not just the surgery itself causing this. Opioids are the silent saboteurs.

When you take morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl after surgery, they don’t just block pain in your brain. They also latch onto receptors in your gut, slowing down or stopping the muscle contractions that move food and waste along. Studies show opioids can reduce colonic motility by up to 70%. That’s not a small effect. It’s a full stop. And because most patients get opioids through IV pumps or pills right after surgery, the gut gets hit hard and fast. Symptoms often show up within 24 to 72 hours. By then, it’s already started.

How Opioids Break Your Gut’s Natural Rhythm

Your digestive system runs on signals-nerves, hormones, and chemicals talking to each other. Opioids throw all of that out of sync.

First, they activate mu-opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus, the network of nerves that controls gut movement. This shuts down the signals that tell your stomach and intestines to contract. Without those contractions, food doesn’t move. Fluid builds up. Gas gets trapped. You feel full, even if you haven’t eaten.

Second, surgery itself causes inflammation. Your body releases cytokines-tiny inflammatory signals-to heal the cut tissue. But those same signals also slow down gut motility. Opioids make this worse. They don’t just act on nerves; they amplify the inflammation response in the gut lining.

Third, your body releases its own opioids during surgery. These endogenous opioids, released as part of the stress response, add to the problem. So even if you don’t get any pain meds, your body is already slowing your gut down. Add prescription opioids on top, and you’re stacking the deck against recovery.

What does this look like in real patients? Hard, dry stools. Straining. Bloating. Feeling like you need to go but can’t. Up to 81% of patients on opioids report constipation. Nearly 60% say they feel like they never fully empty their bowels. And for many, this isn’t just annoying-it’s dangerous. Prolonged ileus can lead to infections, pneumonia from vomiting, or even needing a feeding tube.

Traditional Treatments Don’t Work-Here’s What Does

For years, doctors treated POI the same way: put in a nasogastric tube to suck out stomach fluid, wait it out, and hope the patient gets hungry enough to eat. But studies show this approach barely helps. A Cochrane review found nasogastric tubes only cut recovery time by 12%-barely better than doing nothing.

Modern guidelines have shifted. The focus is no longer on managing symptoms-it’s on preventing the problem before it starts.

One proven fix: peripheral opioid receptor antagonists. These drugs block opioids from acting on the gut without touching pain relief in the brain. Alvimopan and methylnaltrexone are the two main ones. Alvimopan, taken orally, reduces time to first bowel movement by 18 to 24 hours after abdominal surgery. Methylnaltrexone, given as a shot, works even faster in patients who’ve been on opioids for a while. In one study, patients got out of the hospital nearly a day earlier.

But these aren’t magic bullets. They cost $120 to $150 per dose. And they’re not safe for everyone-patients with a bowel obstruction can’t use them. That’s why they’re not used in every case. They’re reserved for high-risk patients: those having major abdominal surgery, or those who’ve never taken opioids before and are likely to get hit hard.

The Real Game-Changer: Multimodal Pain Control

The best way to avoid opioid-induced ileus? Don’t rely on opioids at all.

That’s the core idea behind Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols. Instead of giving opioids as the main painkiller, ERAS uses a mix of non-opioid drugs that work together. Think acetaminophen (Tylenol), ketorolac (a strong NSAID), and regional nerve blocks like epidurals or spinal anesthesia.

One study showed that when patients got acetaminophen and ketorolac before and after surgery, their POI rate dropped from 30% to 18%. Another found that using an epidural cut ileus duration from 5.2 days to just 3.8 days in hip surgery patients.

Even small changes help. A 2022 analysis of 347 patients showed that when nurses started giving IV acetaminophen every 6 hours, encouraged chewing gum four times a day, and got patients walking within six hours of surgery, average POI time dropped from 4.1 days to 2.7 days. Chewing gum? Yes. It tricks your brain into thinking you’re eating, which signals your gut to start moving again.

These aren’t fringe ideas. They’re now standard in top hospitals. The ERAS Society recommends keeping opioid use under 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) in the first 24 hours. That’s about three 10mg oxycodone pills or less than one IV morphine dose. Above that, POI risk jumps sharply.

Who’s at Risk-and How to Spot It Early

Not everyone gets POI. But some patients are far more likely to. High-risk groups include:

- Patients having abdominal or colorectal surgery

- Those who’ve never taken opioids before (opioid-naive)

- People over 65

- Patients with diabetes or previous bowel issues

- Those getting more than 50 MME in the first 48 hours

And here’s the kicker: patients who get over 50 MME in the first two days report 3.2 times more bloating and take over three full days longer to pass their first stool than those under 20 MME.

Early signs matter. If a patient hasn’t passed gas by 72 hours, or can’t drink 1,000 mL of fluid within 24 hours of symptoms starting, it’s time to act. Hospitals using ERAS protocols track these metrics daily. Nurses check for flatus, bowel sounds, and oral intake. If the numbers are off, the team adjusts pain meds, adds a peripheral antagonist, or ramps up mobility.

One hospital in Michigan found that when they started daily "POI rounds"-where surgeons, anesthesiologists, and nurses reviewed each patient’s bowel status-they cut average hospital stay by 1.8 days. That’s not just better care. It’s $2,300 saved per patient.

Why Many Hospitals Still Get It Wrong

Even with all the evidence, many places still rely on old habits. Why?

First, anesthesia teams are used to opioids. They’re easy. They work fast. Changing that takes training-and resistance. One study found 63% of hospitals struggled with anesthesia staff clinging to opioid-heavy protocols.

Second, nurses aren’t always trained to push mobility. Walking after surgery sounds simple, but if staff don’t know it cuts ileus time by 22 hours, they won’t prioritize it. Early data showed only 42% of nurses followed early mobilization guidelines.

Third, cost and access vary. Academic hospitals have the resources for ERAS teams, specialized meds, and tracking systems. Rural and community hospitals? Often not. In rural facilities, POI lasts an average of 5.1 days-nearly two days longer than in academic centers. That’s not just a delay. It’s a gap in care.

And then there’s the fear of pain. Some doctors worry that cutting opioids will leave patients suffering. But studies show pain scores only rise by 2-3 points on a 10-point scale when opioids drop below 20 MME per day. That’s manageable with acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and nerve blocks.

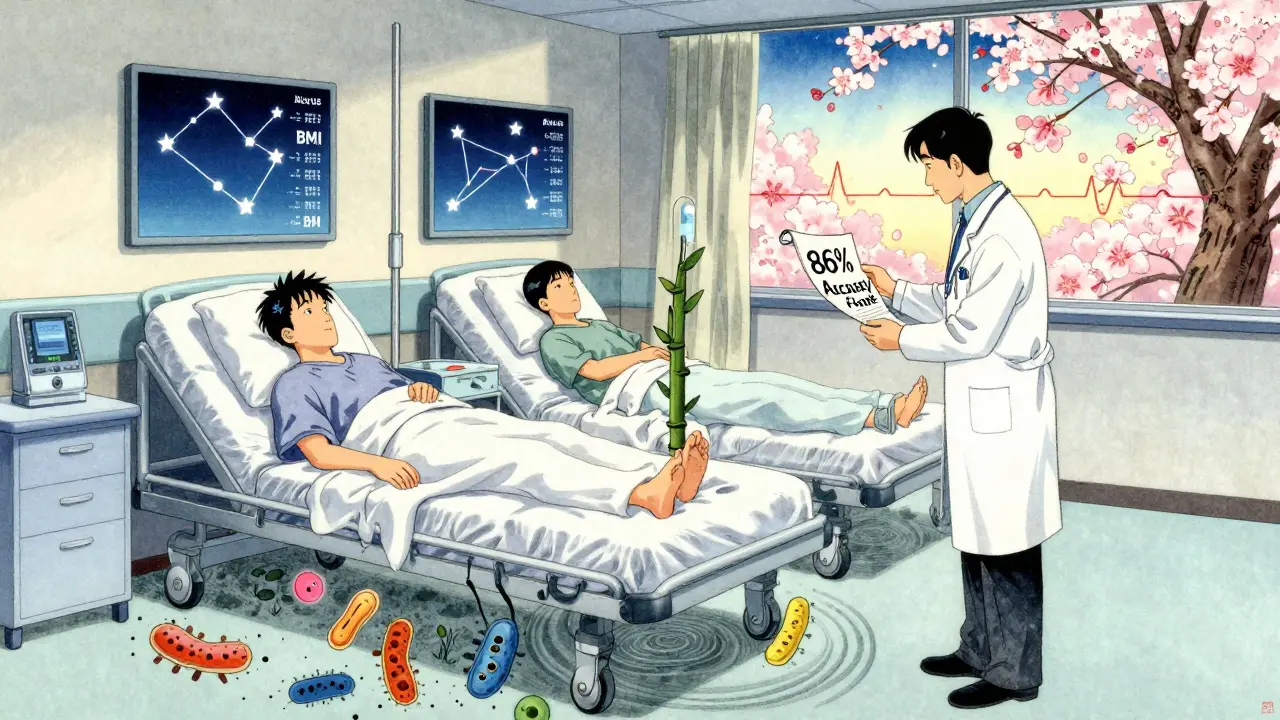

What’s Coming Next: AI, Microbiomes, and New Drugs

The future of POI management is getting smarter.

Alvimopan was pulled off the market in 2009 over heart concerns-but a new extended-release version is now in late-stage trials. If approved, it could be a once-daily pill that prevents ileus without the old risks.

Meanwhile, researchers are testing naltrexone implants that slowly release a gut-specific blocker for days after surgery. And in early trials, fecal microbiome transplants are helping patients with stubborn POI-improving gut motility in 40% of cases.

But the most exciting tool? AI. Mayo Clinic built a model that uses 27 pre-surgery factors-age, BMI, medications, blood sugar, even sleep patterns-to predict who’s likely to get severe POI. It’s 86% accurate. Imagine knowing before surgery that you’re high-risk-and tailoring your pain plan from day one.

By 2027, experts predict comprehensive POI prevention will become standard. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates that if 90% of U.S. hospitals adopt these protocols, we could save $7.2 billion a year. That’s not just money. It’s fewer hospital days, less pain, and faster recovery for millions.

What You Can Do-Before and After Surgery

If you’re scheduled for surgery:

- Ask your surgeon: "Will you use an ERAS protocol?" If they don’t know what you mean, ask about non-opioid pain control.

- Request acetaminophen and NSAIDs before and after surgery-not just opioids.

- Ask if a regional anesthetic (spinal or epidural) is an option. It reduces opioid need by up to 50%.

- Plan to walk the same day as surgery-even if it’s just to the chair. Don’t wait until you feel ready.

- Chew sugar-free gum 4 times a day for 15 minutes each time. It’s free, safe, and proven.

- Track your symptoms: when did you first pass gas? When did you have a bowel movement? Report delays early.

If you’re a caregiver or family member: don’t assume pain meds are the only option. Push for alternatives. Ask if the hospital has a POI prevention checklist. Your advocacy can shorten recovery time by days.

How long does postoperative ileus usually last?

Without intervention, postoperative ileus typically lasts 3 to 5 days. With opioid use, it can extend to 5-7 days or longer. Using multimodal pain control and early mobility, recovery can be shortened to 2-3 days. If no bowel movement or flatus occurs after 72 hours, medical intervention is recommended.

Can you get postoperative ileus without opioids?

Yes. Surgery itself triggers inflammation and nerve changes that slow gut movement. However, opioids significantly worsen and prolong the condition. Studies show POI lasts nearly twice as long in patients who receive high-dose opioids compared to those on non-opioid pain regimens.

Is chewing gum really effective for postoperative ileus?

Yes. Chewing gum stimulates the vagus nerve, which signals the digestive system to start working again. Multiple studies show patients who chew sugar-free gum four times a day after surgery pass gas and have bowel movements 12-24 hours earlier than those who don’t. It’s low-cost, safe, and recommended in ERAS guidelines.

What’s the difference between alvimopan and methylnaltrexone?

Both block opioid receptors in the gut without affecting pain relief in the brain. Alvimopan is taken orally and is best for short-term use after abdominal surgery. Methylnaltrexone is given as a subcutaneous injection and is often used in opioid-tolerant patients or those who can’t take oral meds. Alvimopan reduces recovery time by 18-24 hours; methylnaltrexone by 30-40% faster in some cases.

Are there side effects to peripheral opioid antagonists?

They’re generally safe but not for everyone. They’re contraindicated in patients with known or suspected bowel obstruction (affecting 0.3-0.5% of surgical patients). Rare side effects include nausea, dizziness, or mild abdominal cramping. They do not cause opioid withdrawal in the brain, since they don’t cross the blood-brain barrier.

How do I know if my hospital uses ERAS protocols?

Ask your surgical team directly: "Do you follow Enhanced Recovery After Surgery guidelines?" Look for signs like pre-op acetaminophen, early walking, gum chewing, and limited opioid use. Academic medical centers are more likely to use full ERAS protocols than rural or community hospitals. If they don’t, ask why-and request non-opioid options.

Sangeeta Isaac

January 20, 2026 AT 21:13Jarrod Flesch

January 21, 2026 AT 07:32Kelly McRainey Moore

January 22, 2026 AT 06:21Amber Lane

January 23, 2026 AT 04:47Yuri Hyuga

January 25, 2026 AT 04:32MAHENDRA MEGHWAL

January 25, 2026 AT 23:11michelle Brownsea

January 27, 2026 AT 03:30Glenda Marínez Granados

January 28, 2026 AT 03:07Steve Hesketh

January 28, 2026 AT 07:14Stephen Rock

January 29, 2026 AT 03:40shubham rathee

January 30, 2026 AT 16:45Kevin Narvaes

February 1, 2026 AT 01:47Samuel Mendoza

February 1, 2026 AT 09:03Coral Bosley

February 1, 2026 AT 14:58